Is there a right way to run?

Is there a right way to run? Is it chi? Or is it the pose method? Should we land on our mid foot, heel, or forefoot? There is no perfect way to run, however, like swimming there are some common biomechanical techniques we can learn to develop.

The first thing we learn to do when we start swimming is technique. Otherwise you probably wouldn’t even make it down the swim lane, especially if it’s your first time in the pool. However, it seems there is little to no thought given to running technique. Afterall, we learn to run as soon as we learn to walk. Running is simply a series of single leg hops from one foot to the other. From an early age, PE teachers and various athletic coaches have simply instructed kids to just “go run.” This is totally fine at an early age as children have more hours to play. However, over time this carefree approach to running can lead to injuries because running requires a higher musculoskeletal load as compared to swimming, cycling, and other sports. Then, as adults we start to lose range of motion, particularly in our hips, due to all the sitting we do at our jobs, and even as school-aged students are sitting at desks close to eight hours a day and sometimes sitting even longer at home, we see compromised hip flexors more and more at an early age. In triathlon, running is also the king of injuries because it is fully weight loaded and, therefore, is the predominant cause of muscular damage. Running is a very popular sport with over 28 million people running weekly. Of these runners approximately 56% of these people are recreational runners and as many as 90% of those have an injury when training for a marathon. (13)

Running injuries typically occur for one or more of these three reasons. 1) Running training load progressed too aggressively; 2) Poor running mechanics, especially while fatigued, and; 3) Musculoskeletal integrity was not adequate to handle the training load.

In this article we will address the main principles when it comes to running form and technique. While other smart running coaches and biomechanists may argue and debate the simplicity of the articles I lay out here, the fundamentals of running form I present will be of benefit to most runners and triathletes.

Running Efficiency “Don’t Think, Just Run”

One important concept to keep in mind is that running form doesn’t occur in isolation. Too often we take an isolated approach to our running form. The body is a kinetic chain where one change will likely affect another. It’s important to keep in mind that running is a sequence of contralateral movements. This means, for example, the right shoulder works with the left hip movement. Many running coaches will use various drills in insolation, such as high knees and butt kicks, as if it will fix a runner’s issues and without regard for the interrelatedness of movement.

Sometimes injuries can result from the structure and function of our skeletal or muscular system. Take my own body for example. I’ve been dealing with plantar fasciitis for two plus years now. I always had a really tight right hip and the injuries I’ve dealt with have occurred on the right side. Well, it turns out that my hip socket was out of place. Once that was freed up I have a lot more hip flexibility on my right side and this should lessen my injuries as now my musculoskeletal integrity is much improved.

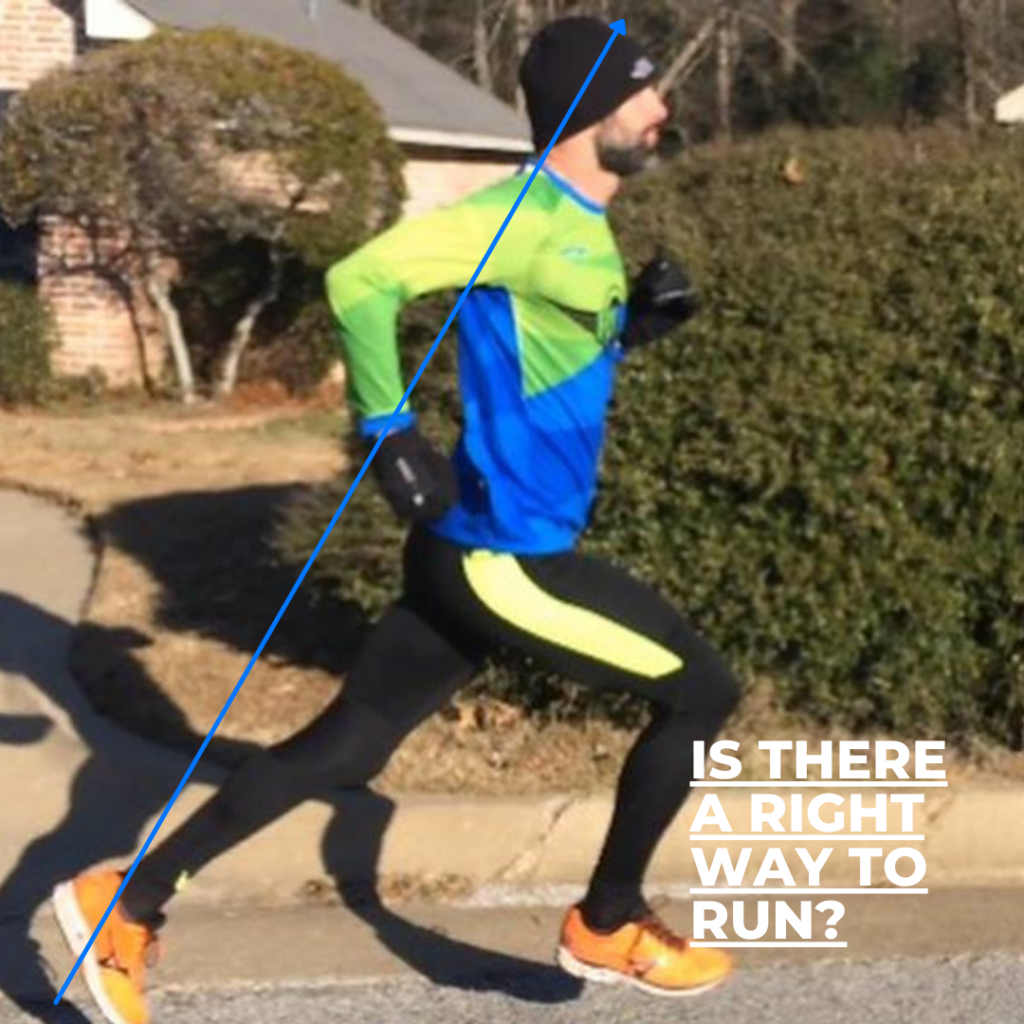

When evaluating someones running form I typically like to start with proper posture when initiating corrections in running form because our legs react to our posture. Without proper posture it’s very difficult for anything else to properly take place such as hip extension and landing.

Running efficiency is not well understood. Oftentimes, we tend to focus on measuring capacities like V.02 max and lactate threshold and improving the aerobic capacity of our engine. While these are good metrics to use for training, one of the key performance indicators is actually running efficiency.

Running efficiency is made up of three types of efficiencies that make up a total efficiency: 1) metabolic 2) neural 3) biomechanical. (10) All three can be improved but for the purpose of this article we will be discussing mostly the third efficiency, biomechanical. This is because biomechanical efficiency relates to the running form as anything that can impact the mechanical “cost” of running, such as wasteful movements. Eliminating these wasteful movements in our running form will also increase our running economy.

An efficient runner can outperform another runner who perhaps has a larger engine (V0.2 Max). Improving your form and, thus, your running economy is often a forgotten element in seeking higher performance. A high V.02 max can be significantly enhanced with improved running economy, by having you run easier at a given pace with a lower heart rate and muscular fatigue. Our running economy can increase when we focus on being relaxed and having good form. Running is a skilled sport, where we want the ability to have good technique on automatic and be able to do it subconsciously. If we are too analytical of our form and think too much then we can become overly stiff and even robotic. Running form is something we need to learn by feel. You can learn by doing running drills such as strides, hill repetitions, and some extended efforts in that V.02 max pace range. Sometimes I like to tell my athletes, “don’t think, just run.” Running by feel should be your greatest strength as a runner. You should strive to learn good technique that is smooth, fluid, natural, light, and springy. Runners have various anatomically unique body types from short limbs to long limbs and everything in between. There isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach for runners.

Posture

When I first address running form at my clinics or with individual athletes the first thing I speak of is posture. You may have had a parent or grandparent tell you to stand up straight with your shoulders back so as to not slump forward. Modern society requires many of us, including both adolescents and adults, to be hunched over desks with rounded shoulders looking at our computers eight hours a day or more. And it’s also worth noting that freestyle swimmers and cyclists are even more prone to rounded shoulders. When we stand tall we create the best biomechanical advantage possible for all other mechanics of our running form.

Similar to swimming, only vertically of course, we want to make ourselves taut and long as possible with a straight line from our chest to hips with our heads in a neutral position. Your head position should have your ears sitting on top of your shoulders. The gaze of your eyes should be approximately 20-35 feet in front of you and your shoulders should be down and not elevated. In cycling, we say where the eyes go the body follows. Similar to all sports, even running, if you’re looking down at your feet then you will likely be leaning too far forward at the hips and hunched over. For ideal posture I should be able to draw a straight line from your head to toe with an ever so slight forward lean that results from the ankles. Regarding shoulders, your shoulder blades should push back slightly to open up the chest without having to arch your back.

Athletes Emily Berry and William Ritter demonstrate tall posture with hip extension and a forward lean.

Our overall posture is critical to our running form. Posture is important to running because it will help you with more efficient and effective muscle recruitment, especially with an increase in hip extension. This is essential to preventing injuries because it puts our joints in better positions and if we are in a better position and more effectively recruiting our muscles we then improve our speed and efficiency.

Forward Lean

The forward lean is one of the last things I typically address, especially with beginners as it’s one of the most difficult tasks to master. To learn this technique you want to keep that good strong, tall, and taut posture and tip or lean forward from the ankles as this will put your center of mass (CoM) just in front of you. You want to be sure you do not try to achieve this from bending at the waist and sticking your head out. It’s a very subtle technique but an important one to help you gain consistent momentum. This is primarily improved through practice, running consistently, and running long, gradual hills. The lean is a sensation you have of falling forward and letting gravity give you a slight push forward. When you do this, stand tall and lean subtly from the ankles. To fully master the forward lean you will also need great hip flexion, extension, and loading mechanics. Andrew Simmons (14) mentions practicing with the three stride drill. This is similar to a falling start drill, but you start with one arm and the opposite leg up, fall forward from the ankle and take three strides. This is important to learn the feel of the tilt from the ankles to help you gain consistent momentum. We want to reiterate first a strong, taut posture and avoid bending from the waist or sticking your head out like a goose. Also, do not arch your back and lean too far back either as this can cause your weight to shift backwards. Think of yourself as a plum line, the idea is to keep everything connected in line from head to toe. Ideally the chest should be connected to the pelvis in a neutral line. If you are not running in a neutral position then you’re going to have to have additional movement patterns to compensate.

Arm movement

Arm movement is a critical component to good running form and is often overlooked by everyone except track coaches, who incessantly yell “move your arms.” These coaches may be onto something here. The arms provide balance, power, and rhythm to the stride which improves efficiency. In fact, using your arms properly can provide about 30% of your power. For example, your arms can help you power over hills or increase your run cadence. As Coach Andrew Simmons (14) likes to say, “the arms lead the charge.” If you have a quick and tidy arm carriage then you probably have good leg speed turnover. Having poor arm carriage can be detrimental to your overall leg speed. Improving your arm carriage can help you improve your technique and efficiency.

Generally, your arms should close the arm angle between your biceps and forearms on the upswing as your hands come towards your chest and open the arm angle as you push your elbows back. The arm movement should also occur at the shoulder joint. Typically speaking, since the arms provide balance, what the arms are doing the opposite leg is also subtly and naturally doing. This is part of the reason why some runners experience overuse injuries as they put their bodies through the side effects of a less efficient stride. For example, having your arm too far out in front of your body can cause the opposite leg to overstride.

Common mistakes with arm swing include:

Crossing the midline: When your arms cross the midline in front of your chest the mobility of the hips is disrupted which can lead to an inward rotation of the femur and other biomechanical errors further down the line. Excessive crossover is also often a result from a passive arm drive originating from the torso twisting trying to maintain balance. The arm drive should occur from the shoulder joint. Not only are these mistakes biomechanically problematic but they also waste a lot of energy, thus reducing your running efficiency. What the arms tend to do indirectly affects what the legs are doing.

Low arm swing: Swinging the arms too low below the waist can cause slower leg speed Since the arm swing regulates leg speed. A quick movement of the arms initiates the drive of the leg back to generate power and a higher cadence.

Wild arms: We have all seen the “wild arms” runner. The one we try to avoid for fear of getting hit by their flailing arms if you get too close. Not only is this motion terrible from a biomechanical standpoint but this, too, also wastes a lot of energy.

Reaching too far out: Another error is reaching too far. Trying to extend your stride by reaching with your arms actually causes an overstride from the front end rather than with hip extension.

Having a good arm carriage while running goes back to your overall posture. It’s almost completely darn near impossible to have a good stride (hip extension) if you’re leaning back or your arms are crossing your chest. For good running arms you need tall posture and relaxed shoulders as this will help to avoid excess movement. The back swing action of the arms should include a bent arm at 80-100 degrees. This is when you push your elbow back. When the arms come forward this is called the upswing. In the upswing, instead of reaching far forward with the arms as the legs go back, your hands should go up towards your shoulders with an angle of 20-35 degrees in the arms, swinging your arms tightly near the front of your chest.

Example of two high school runners with great arm carriage on the upswing, by keeping their arm swing nice and tidy near their chest.

To help you with this, either imagine or even practice running with a tennis ball tucked in at your elbows, between your forearms and biceps. Simply tuck your elbows behind your wrist so that when the arm goes back your wrist is in line with your shoulder. This will prevent your arm crossing the midline of your body and when your arm comes forward you want to minimize forward movement as this helps prevent overstriding. The movement should be upward with your arms just slightly over the chest towards the inside, but not crossing the midline. This is important for the arms to swing towards the inside due to the rotation around the spine, particularly the thoracic spine.

The amplitude or the range of movement with which you move your arms will depend on how fast or how powerfully you are trying to run. You can simply drive the elbow back, but don’t purposely try to punch your arms forward as it’s really a waste of energy. The momentum for running is gained by pushing the elbow back to produce forward propulsion. The shoulder, like the hip, has a stretch reflex mechanism with stored energy that acts like an elastic band and springs the arms forward. The arm swing helps regulate the cadence of the legs. A quick arm swing can assist in driving the leg back to generate power.

Hands

Your hands go along with your arms, but I’ve seen several runners who don’t know what to do with their hands. One of the most common issues I see is a floppy hand or wrist. This also leads to poor arm motion as well. Ideally, your hands should be parallel with the wrist and your hands should stay relaxed and similar to the position of holding a chip clip. The movement of your hands should go back by the hip and up to the “nipple”. After reading Andrew Simmons’ “Unlocking Free Speed,” (14) I started employing a “hip to nip”motion with my cross country runners as so many of them have these wild arms discussed earlier.

It’s All in the Hips

The hips play a major role in running form and performance. Simply maintaining strong and supple hips will help with momentum, propulsion, and cadence. Many runners when they land on their feet allow their hips to drop or sink into their stride and this causes deceleration, slower ground contact time, and you have to use massive amounts of energy to overcome this over the course of a run. An excessive hip drop can also lead to numerous injuries. You also want to avoid a “sitting back” posture. Sitting back on your hips like you’re in a chair won’t allow you to get a proper hip extension. Ideally, you would want to project your hips up and forward. You will also need a good amount of hip and glute strength to do this and this takes time with a consistent effort to strengthen your hips and glutes. We want our pelvis to be as neutral and rigid as possible in order for our glutes to contract. As you lift your hips you push the other leg down into the ground. If your hips are dropping you need to include more glute strengthening.

An example of hip drop. Our goal should be about 5% or less.

Another common problem with the hips is hip adduction, when the thigh comes inward or crosses midline between the feet. Hip adduction is associated with anterior knee pain, ITB, stress fractures, and ACL injuries. If you notice your feet are crossing your midline, then you should spend some time running down the sidelines of a soccer field as you work to keep the legs on each side of the line without crossing over.

Are you Over Striding?

There are two variables that we will get into in our next article that affect running and they are stride rate and stride length. They are directly impacted by the stretch shortening cycle (SSC), which is an important element to a runner’s stride. The SSC is when a muscle is actively stretched or pulled back and then released like a sling slot. The greater and faster the muscle is actively stretched the faster the runner will run because there is more energy stored that is subsequently released.

An excellent stride is a stride that feels perpetual and economical and that includes a strong knee drive with the heel returning towards and underneath the butt that drives the knee forward before landing and driving you forward. The strong knee drive in this stride is mostly passive because of the hip extension launching the heel back like a slingshot which then returns toward and under the butt which assists in driving the knee to drive you forward. Forcing these mechanics results in just wasted energy.

One of the most common errors in runners’ form is overstriding. A stride in front of your body will return a force of 6-7 times your body weight. As your leg is fully extended in front of you when you land, your joints from your ankle all the way up to your knees, hips, and lower back compress. Typically, if you can see your foot when you’re landing you are overstriding. One thing to note is that the overstride of running is a total body movement and one movement affects the other. That said, if you include a subtle to significant knee drive and good heel return with dorsiflexion you will find that overstriding is difficult to do. We will discuss the landing phase and cadence later, but ideally you want your foot to land almost underneath your center of mass with your shin vertical to the ground.

With your stride you want to optimize between vertical and horizontal movement to be able to cover maximum distance with each stride. If your foot lands beneath the body you will get too much vertical bouncing and if you land too far back you will get too much horizontal movement and not enough air time. Unfortunately there isn’t an ideal angle of where your stride should land for everyone. Some runners will use too much of their lower leg swinging it out in front of them with a knee drive that is too low for their given pace. That will cause some overstriding. Judging the horizon is one way to tell if you are getting too much vertical oscillation. If the sky to you looks like it’s dramatically moving up and down then like you are pushing too much underneath you. You want your foot to land under the flexing knee just ever so slightly ahead of your center of mass with your shin vertical to the ground.

Now that you know how to improve biomechanical running economy through the use of your arms, hips, and posture. In our next upcoming article we will take you further through explaining the gait cycle and steps you can further use to develop your own run form.

ABOUT WILLIAM RITTER

Ritter, from Tyler Texas, is the Head Coach at Fly Tri Racing. He is a TrainingPeaks Level 2, Ironman U, Tri Sutto Coaching Certified, USA Cycling, and USA Track and Field Level 2 Endurance Certified Coach and USATF Cross Country Specialist. He specializes in coaching triathletes and runners of all abilities. Ritter’s coaching is detailed and based on the individual athlete blending the art and science of coaching. To learn more about Ritter and personal coaching visit www.flytriracing.com.

Resources

- The Running Gait Cycle Explained, https://www.runnersblueprint.com/running-gait-cycle/#:~:text=Mid%20Stance,foot%20is%20in%20swing%20phase.

- Baltich, Jennifer, and Christian Maurer. Increased Vertical Impact Forces and Altered Running Mechanics with Softer Midsole Shoes, vol. Plos One 10 (4), no. e0125196, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125196.

- Breine, Bastiaan, et al. Initial foot contact patterns during steady state shod running. 1 ed., vol. 5, Footwear Science, 2013, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/19424280.2013.799570#.Ugp07JIm0sc.

- Coyle, Daniel. The Talent Code: Unlocking the Secret of Skill in Sports, Art, Music, Math, and Just About Everything Else. Highbridge Company, 2009.

- Daniels, Jack. Daniel’s Running Formula. 2nd ed., Human Kinetics, 2005.

- Dicharry, Jay. Running Rewired: Reinvent Your Run for Stability, Strength, and Speed. VeloPress, 2017.

- Dierks, Tracy A. “Pronation in runners: Implications for injury.” Lower Extremity Review, June 2011, https://lermagazine.com/article/pronation-in-runners-implications-for-injury#.

- Dixon, Matt. The Well Built Triathlete. Boulder, CO, Velo Press, 2014.

- Fitzgerald, Matt. 80/20 Running: Run Stronger and Race Faster by Training Slower. Penguin Publishing Group, 2014.

- Magness, Steve. The Science of Running. Origin Press, 2014.

- Mateo, Ashley. Should You Change Your Stride Length? Runner’s World, 2020, https://www.runnersworld.com/training/a32907031/stride-length/.

- Runner’s Connect. Running Form Course. www.runnersconnect.net.

- Schubert, Amy, et al. “Sports Health.” Influence of Stride Frequency and Length on Running Mechanics, vol. v.(6) 3, no. May, 2014, pp. 210-217. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4000471/#:~:text=Running%20is%20a%20popular%20activity,the%20United%20States%20run%20weekly.&text=Approximately%2056%25%20of%20recreational%20runners,running%2Drelated%20injury%20each%20year., PMC4000471.

- Simmons, Andrew. Unlocking Free Speed. 2020.

- Thompson, Dave. Conventions for naming parts of the gait cycle, https://ouhsc.edu/bserdac/dthompso/web/gait/terms.htm.