What’s the Big Deal with Aerodynamics?

- Post author:webadmin

- Post published:October 18, 2020

- Post category:Cycling / FTR Blog

- Post comments:0 Comments

An aerodynamic position on the bike is a hallmark of triathlon racing. Here’s how to find the best setup for you.

As featured on TrainingPeaks.

As most triathletes know, improving aerodynamics is a great way to race faster and get more out of training. Anything you can do to minimize your exposed areas and reduce drag will reduce the calories needed at a given power to overcome air resistance—which is crucial for anyone who wants to beat previous times or the competition.

Just how important is aerodynamics? Well, if you take two riders pedaling at the same watts, the rider with good positioning can save 2-8 min over an 18-mile ride, and up to an hour in an Ironman compared to a rider with bad bike fit. Some experts say aerodynamics can matter even if you’re moving as easy as 12-14 mph and, of course, the faster you are the more aerodynamics factor into the equation.

Approximately 85% of your power when riding is used to overcome air resistance.10% is used to overcome rolling resistance, and about another 5% is used to overcome the friction of the drivetrain. Fortunately, we can find “free” speed when it comes to aerodynamics optimization, which we’ll discuss below.

Fit Fundamentals

Since up to 85% of aerodynamic drag is caused by the rider, it’s critical to optimize your position on the bike. The key equation to remember is:

Speed = Comfort + Power + Aerodynamics – Friction – Drag.

SADDLE POSITION

The most common mistake that new riders make is sitting on the bike seat like they are sitting in a chair. Not only is this not ideal for aerodynamics, it will also become uncomfortable quickly. To get a more comfortable and aerodynamic position, you’ll want to rotate the pelvis forward as much as you comfortably can. This sounds horrible, I know, but I promise as you learn this new position you’ll see that it’s remarkably more effective for speed and comfort, and can take some of the tension off your spine in an aero position.

The right saddle is a personal choice, and you’ll most likely want to try a few before you choose the one for you. Your chamois can also make a difference. If you typically suffer chafing, saddle sores and numbness, you may want to avoid using a bulky chamois, as it can actually bunch up in pertinent areas causing more discomfort than relief. A very thin chamois that can dry quickly, like those found in triathlon shorts, may also help you sustain your aerodynamic position comfortably.

BACK TYPES

For a long time now, John Cobb has been one of the most sought-out fitters in the world. He is often referred to as “Mr. Wind Tunnel” and is famous for working with Lance Armstrong in his early Tour de France years, as well as many other top pro triathletes. John uses physiological markers and muscle firing points to help determine body position power, then works from there. He classifies riders into two distinct position types (“A Back” and “B Back” riders) to help inform his decisions.

Only about 25% of riders are classified as “A Back” riders. They tend to be generally more athletic and have good flexibility in their mid and lower backs. Compressing the A Back’s hip angle or diaphragm isn’t as much of a concern, as they tend to have the flexibility and strength for this position. They can ride bikes with slacker seat angles (around 74-78 degrees) and be comfortable on the nose of the saddle.

“B Back” riders are less flexible in the lower back, but can still achieve aerodynamics similar to “A Back” riders. These riders will typically have a wider elbow positioning, with the majority of their flexibility coming through their shoulders. This is why a good “lat wing” angle is critical in helping pull the air over their hips, i.e. the latissimus dorsi should be as close to horizontal to the shoulder joint as possible.

John Cobb says the most important thing “B Back” riders can do to improve their aerodynamics is to work on their pelvic rotation—the more forward you can rotate your hips the flatter your back will be. In the meantime, “B Back” riders can utilize a steep seat angle frame (75-82 degrees) or reverse the seat post to open up their hip angle and achieve higher power between the thighs and upper body.

WHAT ABOUT SHORTER CRANKS?

Many riders still think you need longer levers to produce power—but this isn’t the case. Shorter cranks have no impact on power output, and can improve your aerodynamics at the top of the pedal stroke, as well as give you more space around your diaphragm for breathing. If your hip angle is so tight at the top of the pedal stroke that you’re struggling to breathe, shorter cranks might be a solution.

SHOULD YOU SLAM YOUR STEM?

#slamthestem was a popular hashtag a few years ago among fitters and riders. John Cobb is almost notoriously known for slamming the stem, and bike fit guru Phillip Shama, of Shama Cycles in Houston followed suit.

For the most part, slamming or lowering the front end of the bicycle can lower your head position, thus reducing frontal drag—but of course, there are consequences. Slamming your stem can create an unstable position, and may be unsustainable for a given distance. If you notice uncomfortable tension in your shoulders or neck, or that your vision is obstructed, you may want to try a taller position to start, and work your way lower as you train more.

Finding A Sustainable Position

Which brings us to the next important factor in aerodynamics: you also need a position that is sustainable for your event duration. You can have the most aerodynamic position in the world, but if you can’t hold the position for the duration of your event, you’re going to lose a considerable amount of time coming up out of your position to stretch and readjust.

Matt Stenmetz of 51 Speed Shop says, “Comfort is defined as the ability to sustain your position for the duration for your event. If you’re unable to sustain or hold your position because you’re uncomfortable, nothing else matters.”

Remember, the time trial/triathlon position is not a natural one for the body. Over time as you work on your flexibility and training, you may be able to sustain a more aerodynamic position—but forcing yourself into that position when it’s too uncomfortable to hold will ultimately make you slower. Here are some other important factors to consider:

SAFETY AND STABILITY

“When it comes to aerodynamics and riding a bicycle, it’s more than lowering the front end of the bike or taking out all the spacers,” says Barry Anderson of Cyclologic. The first principle is that the rider’s position needs to be stable on the pedals and saddle. You want to be able to push power from both sides of the bike.

A stable position is also a safe one. Remember that your position and component setup may affect your bike’s handling—for example a large stack between headset and aerobars can cause the rider to understeer the bike. You also need to make sure that you can see down the road—time trialists may be able to just put their head down and hammer, but as a triathlon (and presumably for training outdoors) you need to be aware of cars and other riders.

BREATHING

Another key factor is the ability to breathe. When a rider is in an aggressive aerodynamic position, the diaphragm can be compressed, causing heart rate and ventilation to increase, and adding stress to the overall system. Remember, you still have to be able to run off the bike, so you’ll want to balance efficient breathing against any aerodynamic gains.

What about Gear?

It’s true that you do still have to pedal the bike, but your equipment choices can save you significant time, watts, and energy out on the course. Cycling and triathlon are far from being inexpensive sports, so here we’ll discuss where you can get the biggest return on your equipment investment.

CHOOSING A BIKE

First, to save you some pain, discomfort, and buyer’s remorse, seek out a knowledgeable bike fitter before you purchase your bike. A good fitter will be able to match up your body geometry to the frames that will fit you the best, all while considering your budget. Yes, this will generally cost $200-300, but the money you spend here will save you money and time later.

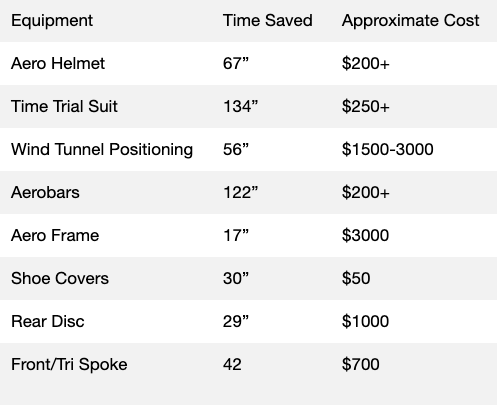

Once you have your new bike frame and are ready to race, you’ll most likely start hunting down some aerodynamic upgrades. Which ones are the most important and least expensive? The table below may help. This table was created from research of Barry Anderson’s time in the wind tunnel:

Time saved over 40k Time Trial

Table based on Barry Anderson’s Research

CHOOSING YOUR UPGRADES

I started racing with a basic road bike, and during my first sprint triathlon I averaged 21 miles per hour (I may have borrowed some wheels). By my second race (a 40k olympic-distance triathlon) I was using some aerobars I had found on sale for $70, and I averaged 23 mph. If you do the math (and buy your aerobars new), this easy upgrade can save you 122 seconds for $200. This breaks down to $1.64 per second of savings, making this the best financial and performance outcome for your investment.

From there you can work your way up the cost scale as you seek to improve performance. You’ll notice that an aerodynamic frame saves you just 17 seconds over a 40k distance, and can be quite expensive—while an aerodynamic kit is a relatively affordable investment, and can save you over two minutes. Jesse Frank, from the Specialized wind tunnel, says that wearing a wind-breaker on a cool day could easily cost you four minutes in an Olympic distance triathlon, and up to 15 minutes in an Ironman triathlon.

Aero helmets are another good investment. These days there are many models in the market, but whatever your tail preference, you’ll want a helmet that wraps closely around your ears, as a lot of the aerodynamic effects depend on your face, shoulders, and back shapes.

WHEELS

While aerodynamic wheels can add weight, it can usually be offset by aerodynamic gains. A standard front wheel costs about 30-40 watts at 20 mph, while a good aero 3-4 spoke wheel will only cost 15-25 watts, and a full disc wheel will cost you just 5-10 watts. In other words, you can save 10% of your power depending on where you upgrade your wheels. Unfortunately, it’s not as simple as just choosing a disc front and rear. In track racing, this might make sense, but with the wind playing a role in outdoor races, you don’t see many front disc wheels, which can be extremely unstable in crosswinds.

Most conditions, however, will favor at least a rear disc wheel. As always, these decisions will be subject to the conditions on race day, which is when tools like Best Bike Split can help riders make the best call for themselves.

SHOULD YOU SHAVE YOUR BODY?

What about shaving? Jesse Frank from Specialized estimates that, depending on how naturally hairy you are, shaving your legs could save you a minute or more in a 40k race and up to another 12 seconds if you shave your arms. Regarding facial hair, our heads aren’t especially aerodynamic, so shaving facial hair doesn’t make any noticeable difference.

WHAT ABOUT HYDRATION?

Ideally, the Ironman racer will have a bottle tucked between their aerobars and behind the seat post. Bottles behind the seat post are the most aerodynamic, but you have to reach around to grab the bottle, breaking your aero position and essentially slowing yourself down. The best and most practical place to have your water bottle for easy access and to remain in aero position is between your aero bars—sometimes this can even be more aerodynamic than if the bottle wasn’t there! The worst place you can store a water bottle is on the frame, where it will disrupt the flow of wind.

Ultimately your aero position will be a personal journey, balancing what is sustainable, efficient, and reasonable for your body. Remember that your position needs to work for you (and your wallet!) as you strive towards your best performance yet!

SOURCES

http://autobus.cyclingnews.com/features/?id=2006/cunego_windtunnel

https://51-speedshop.com/blogs/news/the-kona-process

https://51-speedshop.com/blogs/news/adapting-to-the-tt-position

http://www.ero-sports.com/2020/index.php/journal/36-triathlon-specific-fit-8

Advanced Aerodynamic Position System. Cobb Cycling. John Cobb,

Wind Tunnel Magic. John Cobb.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11417428

https://www.uci.org/inside-uci/constitutions-regulations/equipment

Wind Tunnel Magic. John Cobb.

Aerodynamic Optimization. Cycologic. Barry Anderson

ABOUT WILLIAM RITTER

Ritter, from Tyler Texas, is the Head Coach at Fly Tri Racing. He is a TrainingPeaks Level 2, Ironman U, USA Cycling, and USA Track and Field Level 2 Endurance Certified Coach and USATF Cross Country Specialist. He specializes in coaching triathletes and runners of all abilities. Ritter’s coaching is detailed and based on the individual athlete blending the art and science of coaching. To learn more about Ritter and personal coaching visit www.flytriracing.com.